How 30 seconds of code is deployed

This is perhaps the longest article I've written, but I feel there's a ton of value to be had from my insights, mistakes, and the evolution of how 30 seconds of code has been deployed over the years. Grab a cup of coffee, and find a quiet spot, as we take a trip down memory lane.

To view the state of the repository at a given time in history, you can visit the Commit Reference and Browse files.

Markdown-only Early December 2017

Tools: Node.js · Commit reference

The original build process involved around the generation of Markdown with all of the snippets ordered and organized as a Markdown file with internal links presented as a page of contents.

Some static Markdown parts were used for the file's header and footer and a builder script would read each file in order and add its contents to an output string. The final result would be written to the repository's README.

Additionally a linter script was also provided to apply some predefined rules (Semistandard) to the code in the Markdown files.

As far as automation went, it was completely non-existent, needing manual script runs and commits for each build.

Earliest website attempts Late December 2017

Tools: Node.js, HTML, Travis CI, GitHub Pages · Commit reference

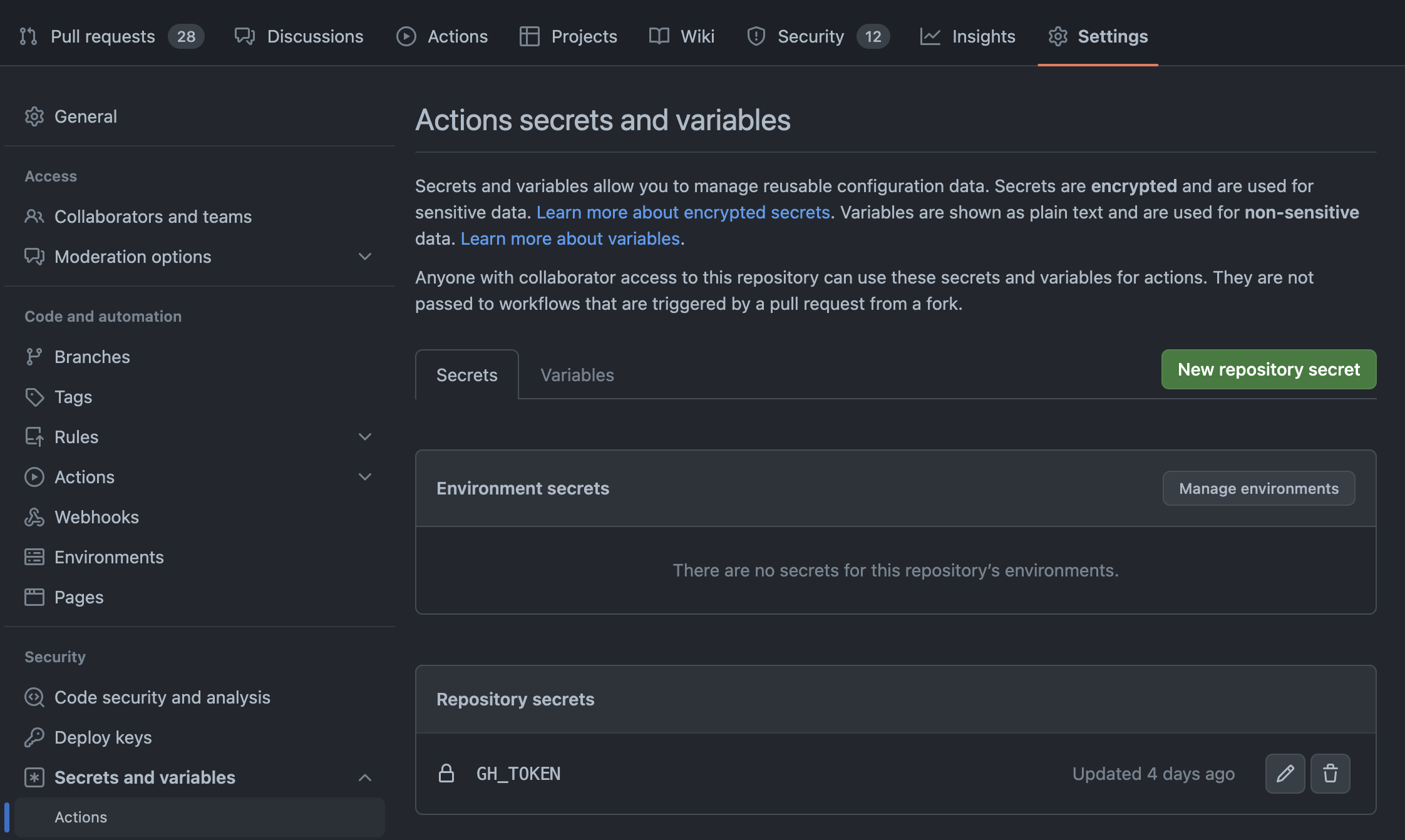

As time went by, the 30 seconds of code bot account (not a real bot) was introduced. The account was used for automation tasks, such as automated builds via the creation of a GitHub Token that was then used to push commits to the repository. The following git push command was what allowed the bot to push new code to the repository:

git push --force --quiet "https://${GH_TOKEN}@github.com/Chalarangelo/30-seconds-of-code.git" master > /dev/null 2>&1Using the token, stored in an environment variable on GitHub, as part of a special URL one can push code from the token authorizer's account to the repository (provided the author has sufficient access). The rest of the command is written in such a way to prevent outputting the token into the logs and exposing a backdoor that anyone could exploit.

For the purpose of automation, Travis CI was used. This allowed changes pushed to master to trigger new builds, as well as other automation tasks. The configuration file for Travis specified which tasks to run (such as linting via Semistandard and Prettier) and scripts to execute.

Tagging was added during that time in the form of a plaintext file, specifying a tag for each individual snippet. A tagging script was added as well, allowing new snippets to be added to the file as uncategorized, which then needed manual processing.

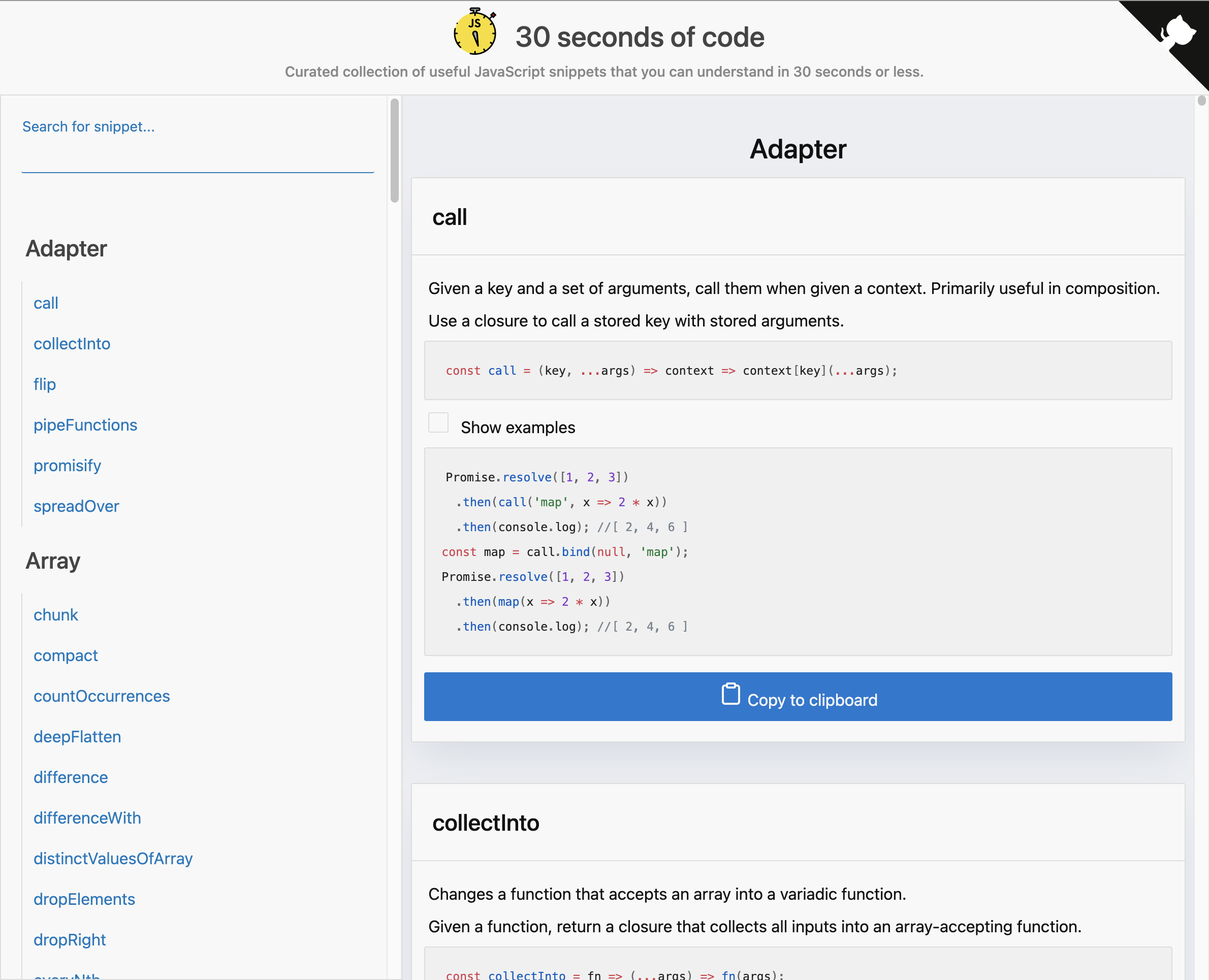

Alongside the previous build script, a new web script was added. It followed a very similar pattern, generating an HTML page, clearly inspired by Lodash's website. The output of the web script was then stored in a directory and deployed automatically on GitHub Pages.

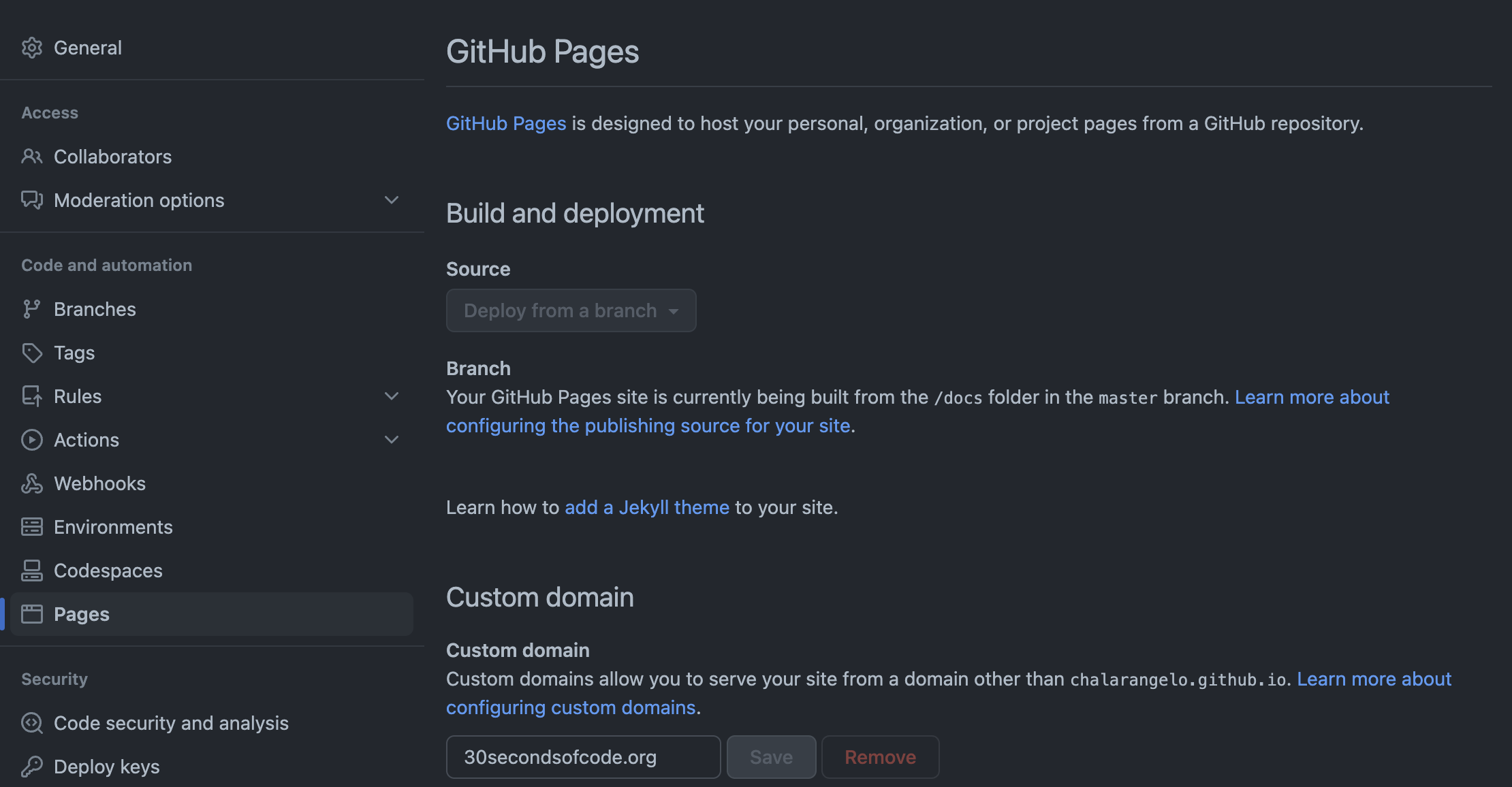

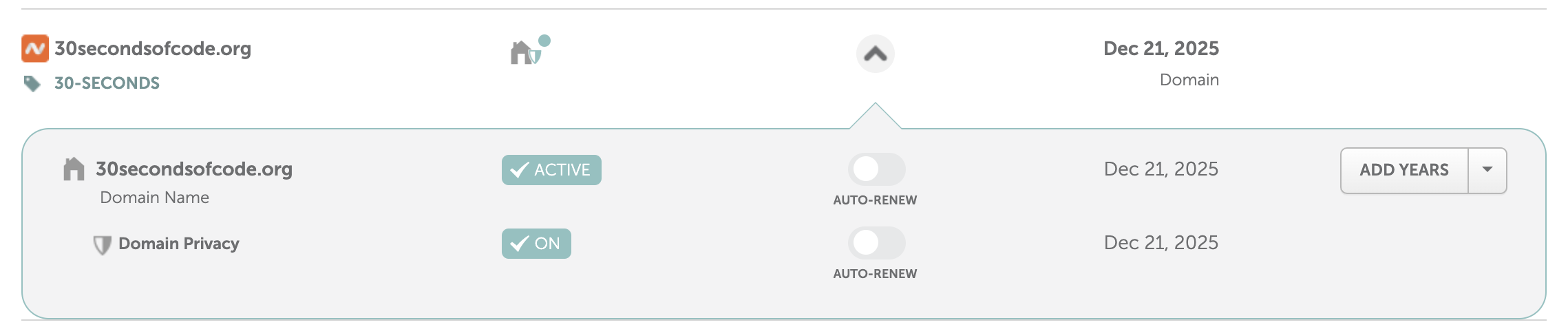

The current domain was obtained during this time from Namecheap, but unfortunately the configuration that was used back then is lost to time.

Trivia

Travis CI was misconfigured for a little while, resulting in Travis builds triggering new builds as soon as the pushed to master. This caused an infinite loop that burned through the entirety of the free credits the project was provided with. Luckily, the Travis team was kind enough to restore them after I messaged them.

GitHub Issues malfunctioned at some point, resulting in the issue counter jumping a few numbers (something like 100). To this day, no incident report has been published and GitHub has not explained what happened back then.

The bot token was originally incorrectly added in plaintext as part of the bash script where it's used. This resulted in a security vulnerability that was identified by someone in a chatroom. Luckily, no malicious actors took advantage of it and I generated a new token after the code was fixed. If I remember correctly, a full rewrite of the master branch was performed to purge the offending commits.

Multi-page website Early to mid 2018

Tools: Node.js, HTML, Travis CI, GitHub Pages · Commit reference

As the project grew, several new ideas were tested. Alongside website build automation, a Rollup script was used to create a JS package with all the code snippets and tap was used to add test cases for each snippet. These were part of the automated workflows running still on Travis CI. The JS package was also released on npm, but was discontinued at a later time.

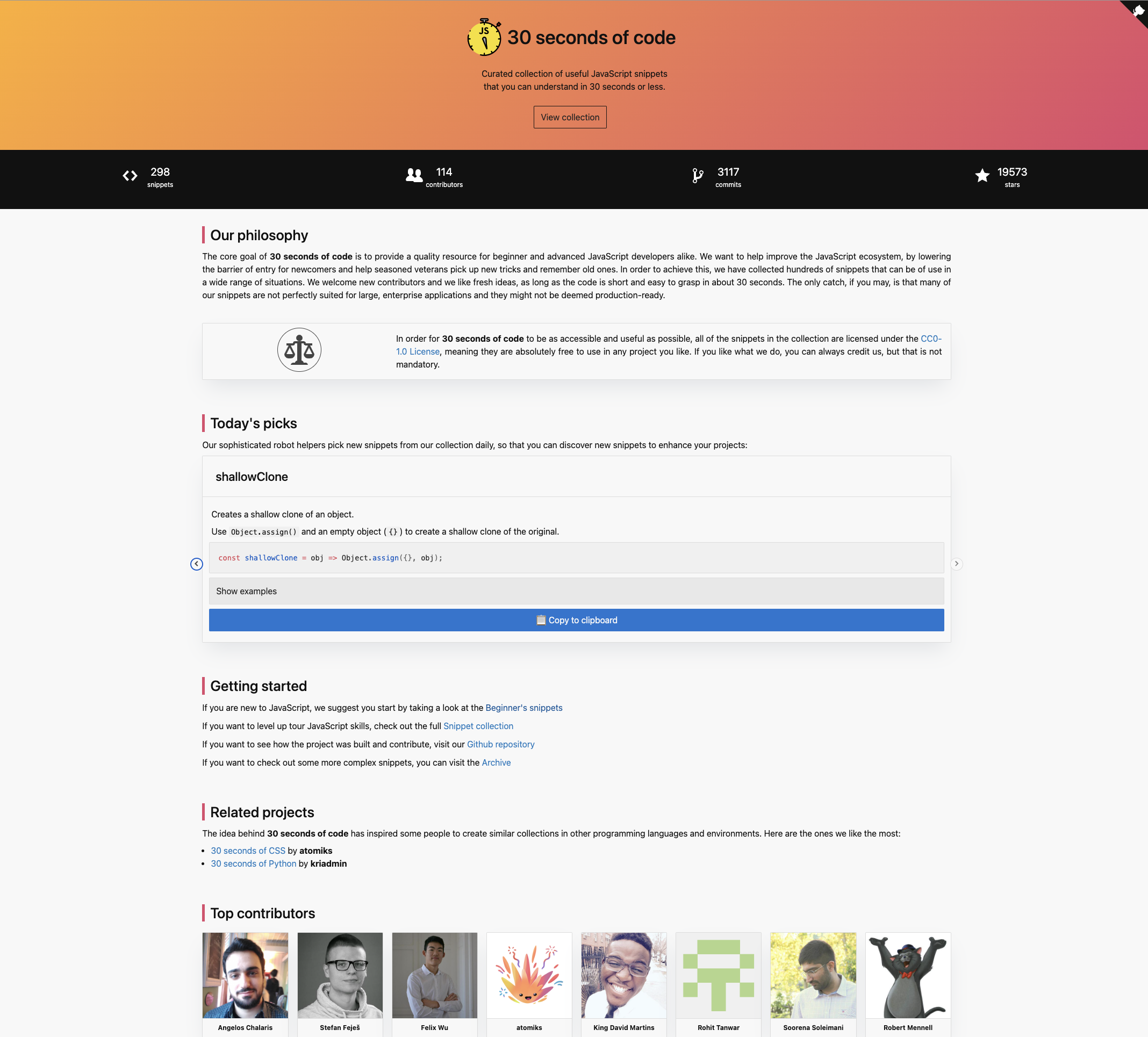

New static parts were added to split the page into multiple pages at this point, and a redesign was implemented to make the page a little better visually, showcasing statistics and contributors. Some dynamic content was added, such as daily picks on the homepage and data retrieved via GitHub's API, using a GitHub token same as other processes.

Finally, Travis CI was set up to run using a cron job schedule as well as push events on the master branch, allowing for daily builds to occur at a predetermined time.

Trivia

2018 was a year of experimentation. New side projects came and went, such as a localization effort, a JS glossary and a snippet archive. Traces of these experiments can be found in the commit history of the repository.

At this time, the website was only comprised of the JS snippets and nothing else. Similar projects for CSS and Python were actively supported by some of the contributors, but had full autonomy to pursue their own paths. This decentralized organization put together without much planning would later come to bite me.

Website facelift Late 2018

Tools: Node.js, HTML, Travis CI, GitHub Pages · Commit reference

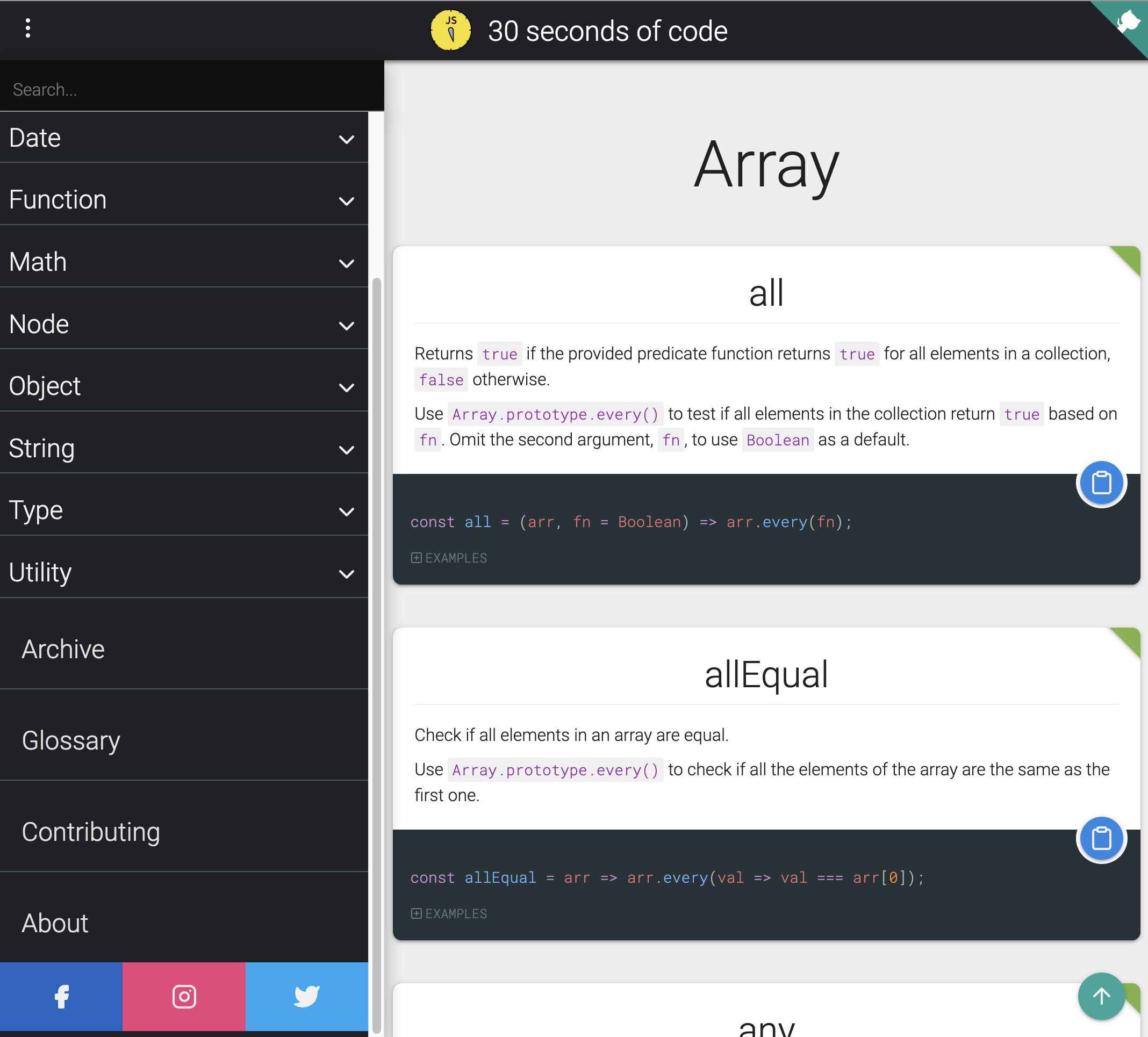

Later in 2018, the website was redesigned yet again. The dynamic parts were removed, the search system was reintroduced and the website style's were finally completely custom, written in Sass.

Not much had changed in the automated workflows, except for the introduction of some intermediary steps. One such step was the creation of a JSON file via the extractor script, which could then be used as the data source for other tasks. The Travis CI configuration file now contained about a dozen scripts and this was a way to speed up a lot of them.

Another experiment that was running at the time was a snippet collection for VS Code, generated by another script. Unfortunately, publishing the collection could not be automated and required a very slow process every time a new version needed to be published. This was also discontinued later down the line.

Trivia

DigitalOcean sponsored the project back in 2018, providing a handful of cloud machines to work with. Unfortunately, this sponsorship was never utilized and the website never got the much awaited snippet API that it was expected to get. Another sponsorship from DigitalOcean came through the next year, but unfortunately it suffered the same fate.

Gatsby introduction Late 2019

Tools: Gatsby, React, Travis CI, Netlify · Commit reference

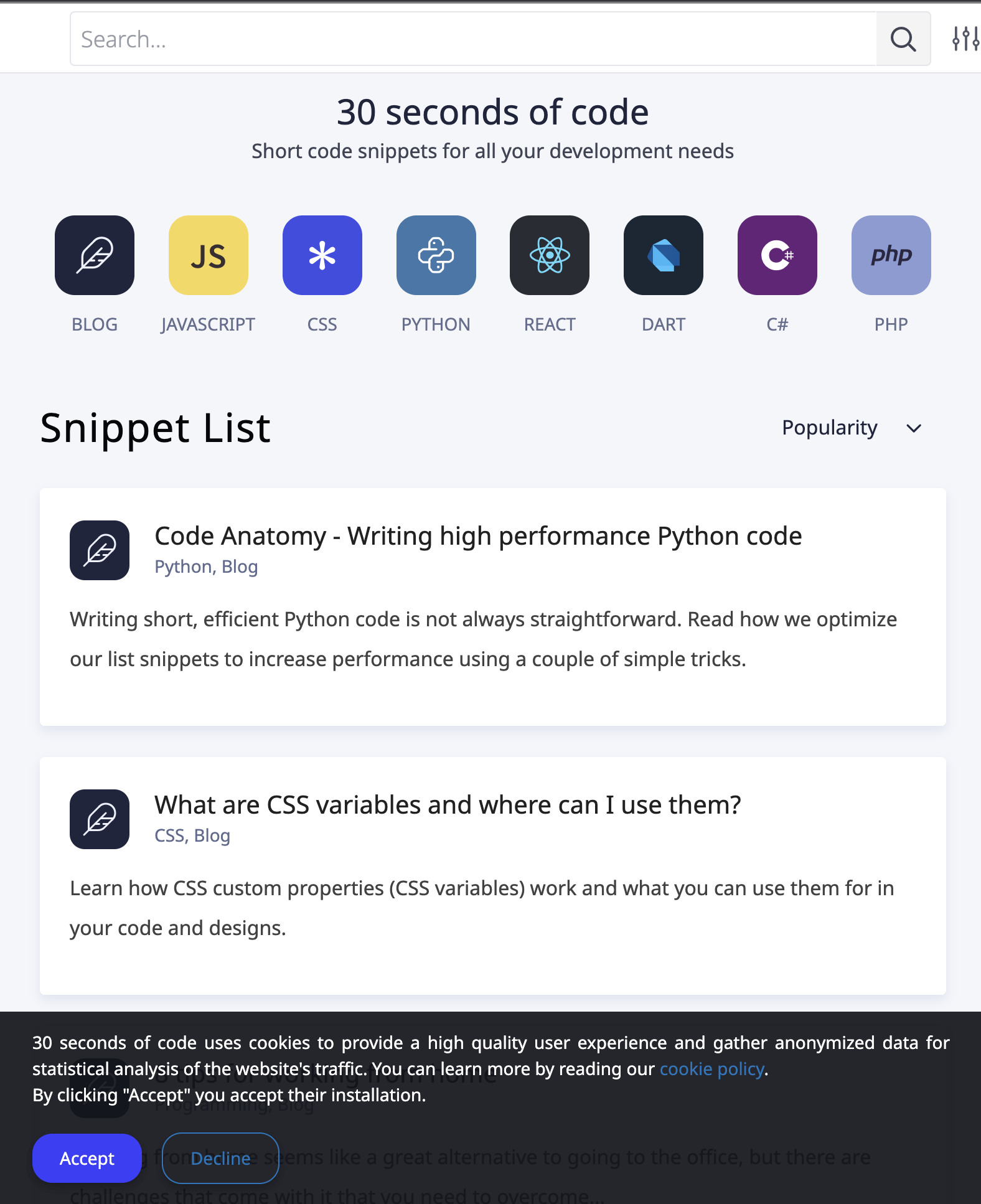

The first half of 2019 was mostly quiet. However, during the summer months, Gatsby was all the rage, so naturally 30 seconds of code followed the hype. It was also a great opportunity to move towards using React instead of plain HTML, which was getting hard to work with.

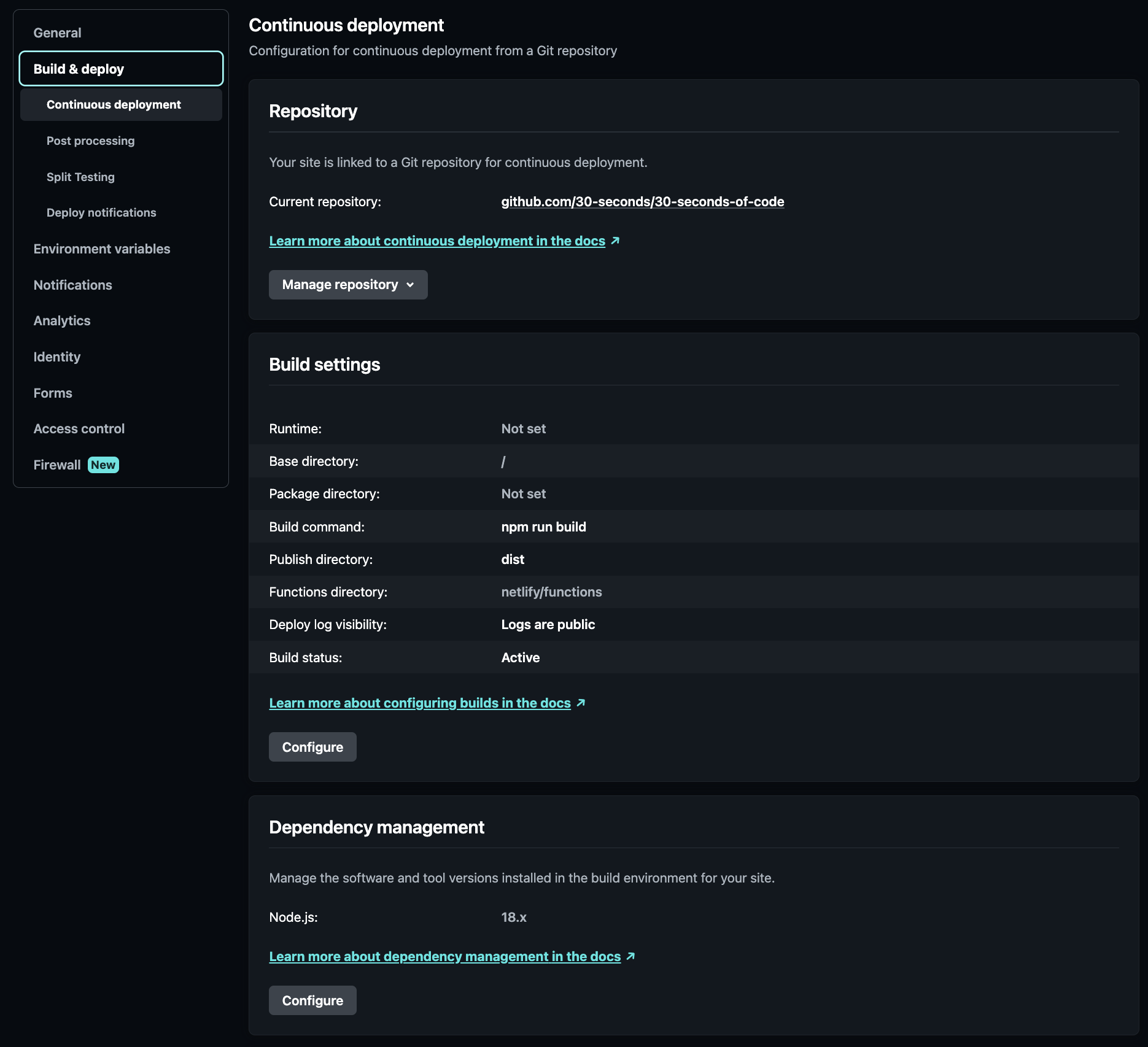

Instead of GitHub Pages, Netlify was now the platform where the website would be deployed. This proved to be a good plan, as it allowed Travis CI to execute the other scripts, whereas Netlify would run Gatsby and deploy the website.

At this time, most side projects about other languages were starting to fall apart. The 30-seconds organization seemed like the way forward, allowing consolidation of all official repositories and proper maintenance. Some integration tools and a repository starter were provided, allowing new projects to run autonomously.

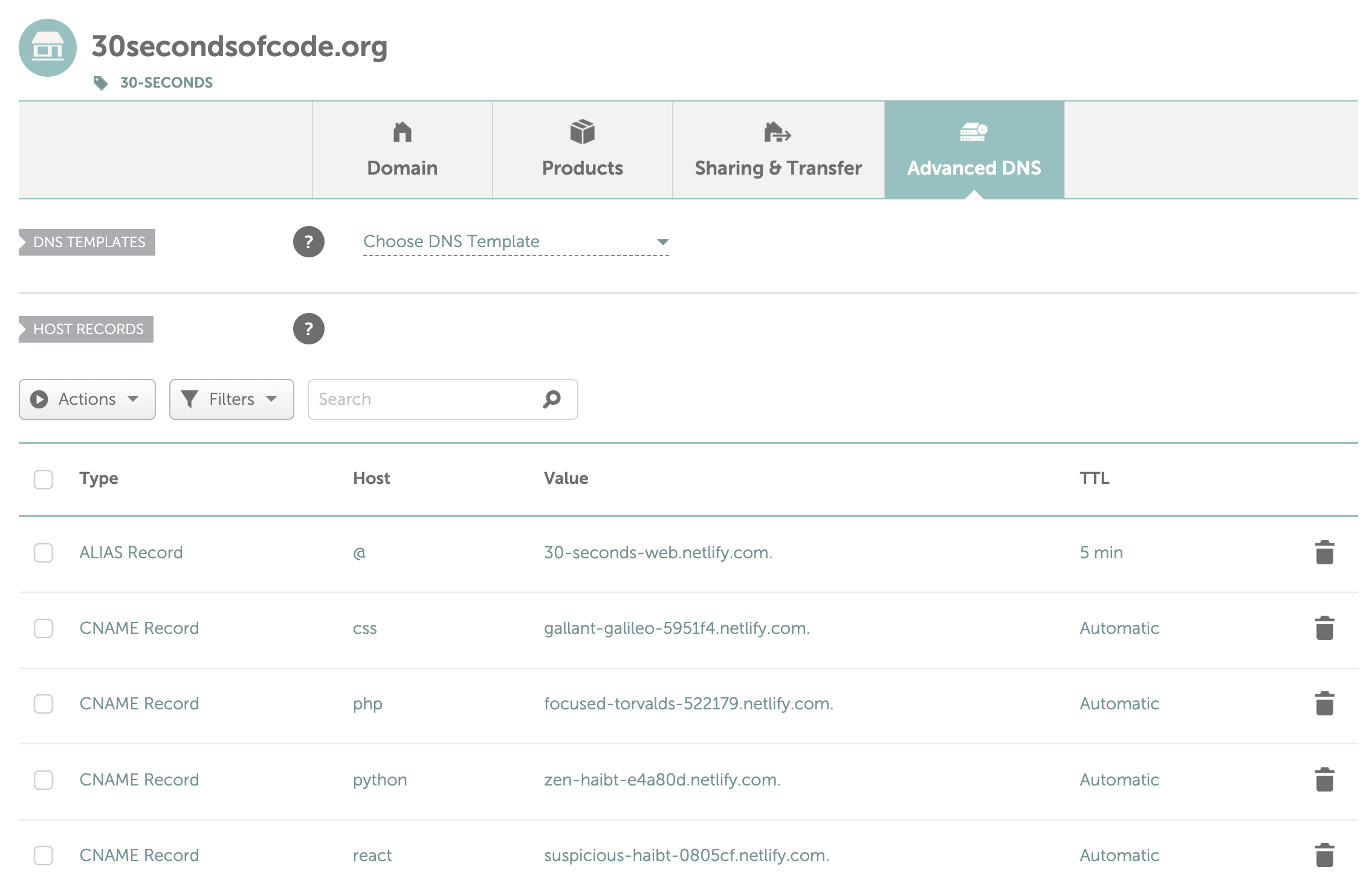

Each repository maintained its own website instance, all under the same domain name, but individual subdomains (e.g. css.30secondsofcode.org). The infrastructure was pretty much the same for each repository, with unique elements such as logos and styles being maintained for each project. Subdomains were configured via the Namecheap Advanced DNS menu, linking each Netlify project to an appropriate subdomain.

While this allowed for every project to be presented in a similar manner, it complicated maintenance to the point where a simple text change would require 5 or more commits across different repositories. This was definitely non-feasible in the long-term.

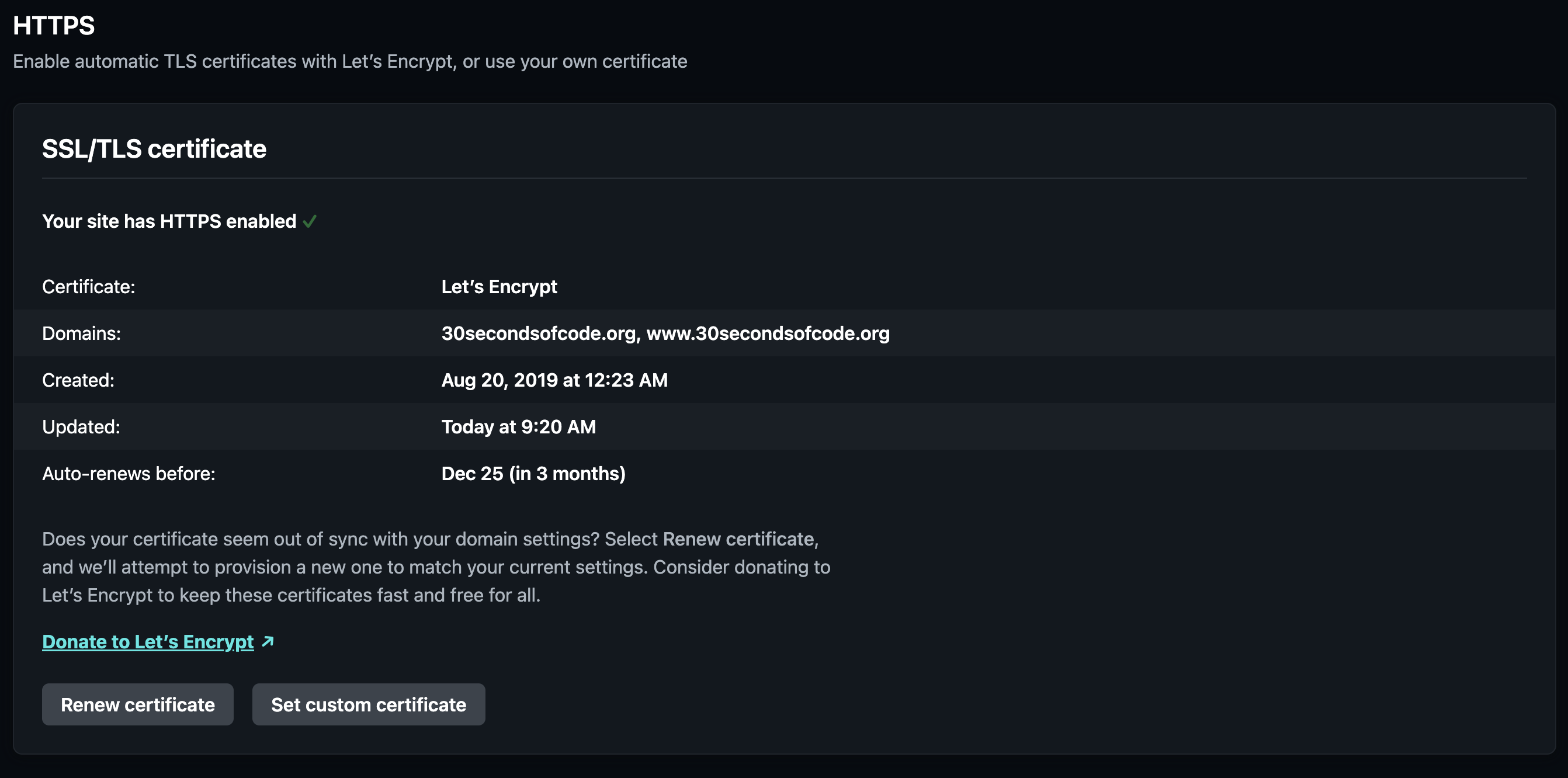

At around this time, HTTPS was becoming mandatory for all websites to be trusted by users and browsers. I'm not 100% certain how I obtained my SSL certificate before this time (I think I used Cloudflare at some point, but the details are lost to time), but Netlify is kind enough to provide you with SSL certificates for each website for free. Obviously, I used their service as soon as it was available to me and never looked back.

Trivia

A lot of commits during that time are from unrelated histories (other repositories). You can probably tell by looking at the README logo, which features a different 30 seconds stopwatch for each project.

Getting the rights to all the repositories was not easy. Some maintainers wanted to retain their autonomy, others were completely indifferent and some were nowhere to be found. One of the repositories' original owner had disappeared from GitHub and it took a lot of searching to track the down on Reddit and ask them to transfer the repository to the organization. Luckily, nobody had any issues with the transfer and the organization filled up with content.

During this time or a little while later, Travis CI was starting to move away from its free forever model, making it harder to keep using. Eventually, credits ran out and Travis CI was dropped entirely from the infrastructure.

Website consolidation Early 2020

Tools: Gatsby, React, Travis CI, Netlify, Git submodules, GitHub Actions · Commit reference

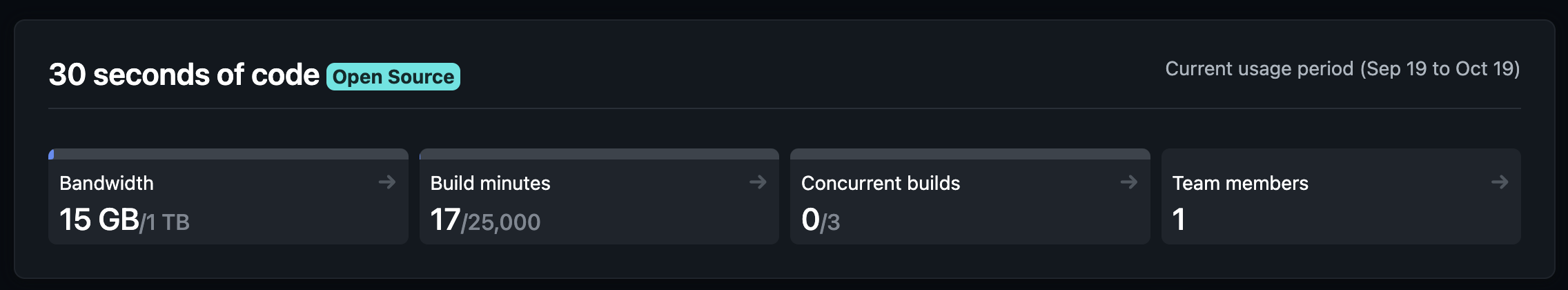

After contacting Netlify in late 2019, a generous Open Source sponsorship was provided. This matched their Pro plan, which allowed for far greater flexibility and expanded limits.

As mentioned previously, maintaining a handful of repositories and websites was close to impossible. The decision was taken to move the website infrastructure to its own repository (30-seconds-web) and use Git submodules to fetch the content repositories at build time.

As GitHub Actions were available at the time, it was decided that deployment to Netlify would be triggered via pushing to the production branch. This would ultimately result in the deployment action adding an empty commit to the branch and forcing it to update. Netlify would then trigger a build from the branch and deploy the website.

Git submodules were tricky to work with, but the main advantage was that updating them to the latest commit for each repository was trivial via a script that could run on Netlify.

git submodule update --recursive --remoteWhat this meant was that Netlify could always fetch the latest commits from all repositories and the web infrastructure repository didn't need to do anything. Additionally, development was also pretty simple and fetching the latest snippet data was only a few keystrokes away.

In order to make this work correctly, a prebuild command was added to package.json, performing the content update whenever npm build (the Gatsby build) was run.

Some additional utilities and functionality were introduced at this time, such as a pretty decent search engine, a snippet ranker, a recommendation system etc. Some of these tools are still in use today with minor changes to their code.

Trivia

Some new JS tools were introduced at this time, such as Storybook and Jest for testing, alongside a handful of configuration files and utilities.

Most of the structure and logic of the original setup for the web infrastructure holds true to this day. Due to framework changes, a lot of the current conventions are a jumble of different conventions, picked up from each new tool along the way.

Until the next milestone (pun intended), numerous releases and changes were made to the web infrastructure. These are far too many and complex to talk about and some of the details have faded in my memory. Feel free to browse 30-seconds-web releases prior to v.6.0.0 to check them out for yourself.

During this stage, I had to make some DNS changes, if I remember correctly. To cut a long story short, I made a mistake that meant the website would never go live on my domain. After a very long chat with Namecheap's support, I realized that it wasn't a propagation issue that kept my website down for half a day, but a typo on my part.

Replacing Gatsby with Next.js Early 2021

Tools: Next.js, React, Netlify, Git submodules, GitHub Actions · Commit reference

Gatsby's issues kept on piling up for quite a while. From the inability to upgrade between minor versions to slow GraphQL queries and tons of bugs and broken builds, I sought a better tool for quite some time. Next.js was quite popular at the time and was also based on top of React and supported by Vercel. It seemed like a match made in heaven.

The core philosophy was still almost the same - Git submodules for content fetched by Netlify for Next.js deployments triggered via the production branch scheduled or triggered via a GitHub Action.

Deployments were now triggered by pushes to the master branch or by a cron job scheduled daily. Additionally, a manual trigger was provided to allow for emergency deploys to be made without the need of an extra commit added to .

The extraction process used at the time might be worth explaining briefly, as it ties into the next milestone. A handful of parsers were created to read and parse files, converting Markdown and plaintext into JSON objects. The result of parsing these content files was ultimately some instances of a few JS classes, representing the main entities of the project. Some concepts such as adapters and decorators were borrowed from other frameworks. Finally, serializers would take the enriched data and produce pages for each snippet, along with listings and collections.

On a side note, there's a huge list of redirects that is used by Netlify. This is pretty important for SEO, as it redirects old URLs to new ones. There are lots of artifacts in there, such as language renames, listing sorting removals, snippet renames etc. Take a look for a slice of the project's history.

Another interesting addition is the Twitter bot workflow. This GitHub Action used a JSON file that was randomized each deployment, generated by a script called chirp. This allowed only specific snippets to be eligible and made their information available to the bot that run at specific times to post on Twitter. In order to post to Twitter, certain secret environment variables were added to the repository for the Twitter API and Unsplash API.

Finally, the website's sitemap was generated manually via a script. While Next.js (and possibly Gatsby) provide convenient options to do this, not being bound to the framework except for page generation would prove to be a wise decision.

Custom ORM-like solution Early 2022

Tools: Next.js, React, jsiqle, Netlify, Git submodules, GitHub Action · Commit reference

While the infrastructure was mostly stable, the build process was slow and clunky. Inspired by Object-Relational Mappings (ORMs) (mainly Ruby on Rails' ActiveRecord), I developed jsiqle, which somewhat resembled an ORM approach to what I was previously doing with Object-Oriented Programming (OOP).

While the tool's codebase is very complicated (almost unnecessarily so), the principles are simple. Models are used to model individual entities with specific attributes. These models can then define relationships, methods and derived properties and are grouped together in a schema. Serializers are provided to turn these models into plain JS objects that can be written into JSON files.

Using jsiqle removed a lot of the complexity from the website repository, allowing for simple models and relationship definitions, as well as very clean serializers. An extraction process handles parsing Markdown files into a large JSON (stored temporarily in .content/conten.json) that is then used by the application entry point to populate the in-memory dataset. These two steps in the preparation process could be run separately and the output of the first one could also be easily inspected.

A final step is performed via the use of serializers and writers, storing all content in individual JSON files inside a directory. This is then used by Next.js's helpers to get the paths of each page to generate.

The application entry point in itself contains a lot of magic and complicated code to make development easier and faster. Models, serializers and utilities, for example, are loaded automatically and exposed globally via the Application object, allowing them to be accessed anywhere.

One of the conveniences afforded by jsiqle is the ability to have an interactive Node.js terminal (via the npm console command). This allows developers to query the extracted dataset, much like they can do in the Ruby on Rails console.

Trivia

jsiqle originally stood for JavaScript In-memory Query Language with Events. The "with Events" part is no longer true, though.

Due to the way a lot of the website works, Google Analytics were only loaded if the user has accepted cookies. Some complex and quirky code had been added to send those initial page views, when appropriate.

If you look at the document template for Next.js, you will notice this line (<script>0</script>). To this day, I have no clue why this worked or who suggested it, but it fixed some really obscure server-side rendering (SSR) problem or something similar.

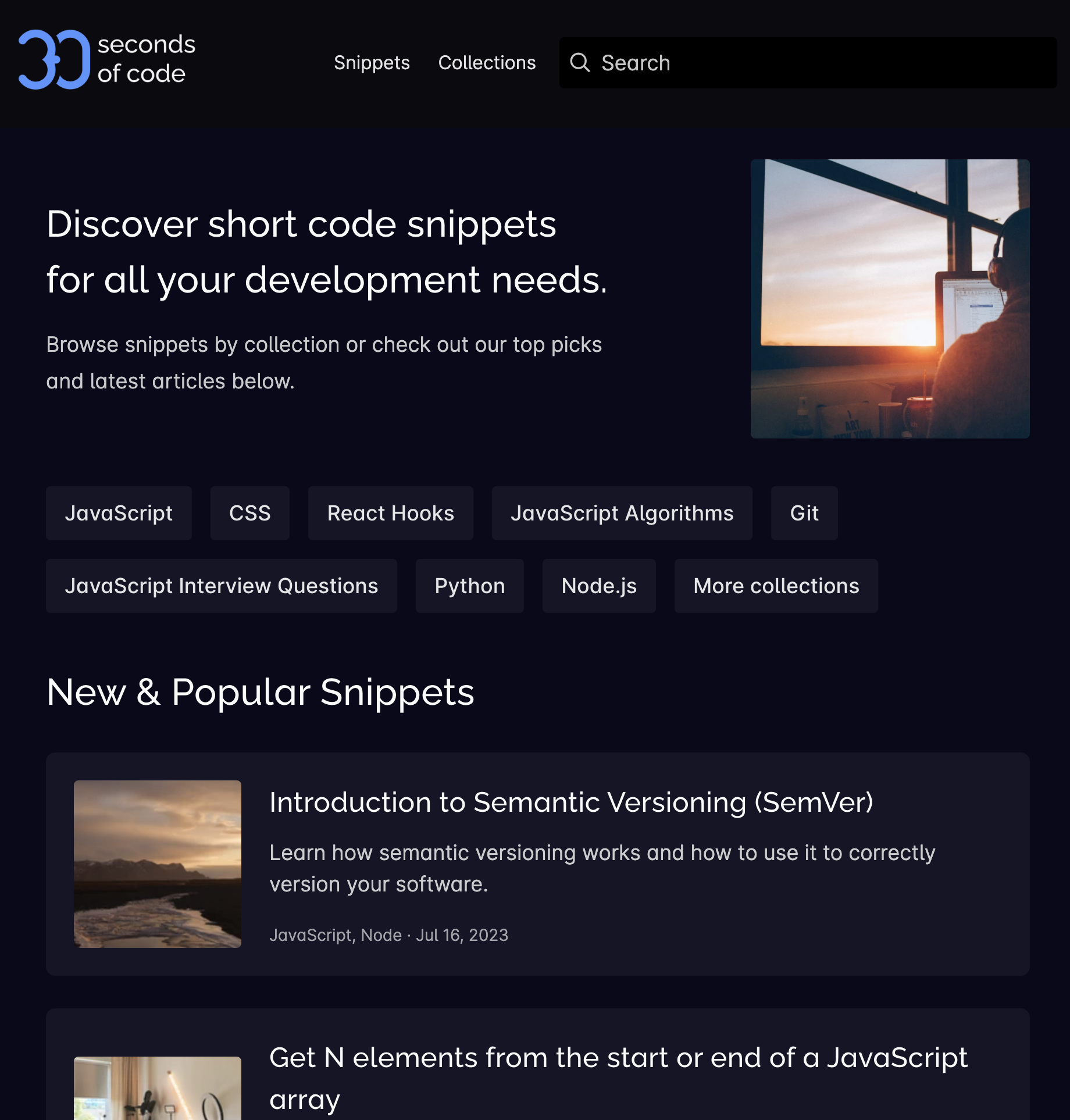

Replacing Next.js with Astro Early 2023

Tools: Astro, jsiqle, Netlify, Git submodules, GitHub Actions · Commit reference

Next.js was starting to get in the way more so than anything else. React was also not necessary in most cases, slowing down the page. A return to static site generation (SSG) was justified, and Astro was the perfect tool, combining flexibility and simplicity.

The migration from Next.js was surprisingly easy and adapting React components to Astro ones didn't take nearly as long as I expected. This resulted in a very similar repository structure and build process as the one before it.

A point of relative interest at this stage would be the omni search component, built using the Web Components standard, allowing for a very dynamic component written in plain JS, without React or other similar frameworks.

As Astro is essentially a templating language with a static site generator built-in, builds were now running faster and the website's performance and SEO were improved.

Speaking of performance, both Astro and Next.js provide some asset optimization tooling, yet I chose to roll up my own. Assets are loaded from a content repository and are then processed via sharp, producing lower resolution images ready for the web, as well as images in the WebP format. These are then stored in a temporary directory (.assets) and used for development, without being regenerated every time the predev command runs (already generated assets are skipped). If the build is in a production environment (Netlify), the assets are also copied to the public directory to be served as part of the website.

Trivia

Initially, I was looking into Svelte and SvelteKit as a replacement for React and Next.js. I stumbled upon Astro by accident and decided to give it a quick try. Surprisingly, I liked it far more than I expected and, due to a very simple migration process, I opted to use it.

Content repository merge Mid 2023

Tools: Astro, jsiqle, Netlify, Git submodules, GitHub Actions · Commit reference

As community contributions were way lower, maintaining a handful of content repositories wasn't justified. Additionally, structural changes to how Markdown files were written required committing changes to 5 different repositories - a problem I was all too familiar with.

Merging all content repositories sounded exciting, yet I had no idea how to do so or if it was even possible. In fact, I thought it wasn't possible at all. Luckily, I found an article online outlining the process. What it all boils down is essentially adding the other repository as a remote locally and merging its master branch into the current master branch with the --allow-unrelated-histories flag.

git merge swtest/gh-pages --allow-unrelated-historiesAfter that point, the website repository's submodules were removed and only one was left in order to allow for the automated content fetching on Netlify to continue as it always did.

Trivia

Merging unrelated histories makes it really hard to follow changes and makes the git tree almost unusable. It also makes issue and pull request references reference the new repository instead of the original one. Don't do it, kids, it's not worth it most of the time.

Website & content repository merge Late 2023

Tools: Astro, jsiqle, Netlify, GitHub Actions · Commit reference

After all the changes back and forth, it was starting to become clear that the separation between website infrastructure and content made little to no sense. The unrelated histories merge strategy was used once again, retaining the exact structure of the website repository. The content directory, previously containing git submodule references, now contained the raw content files.

This change created some new challenges, such as builds only triggering for website code changes and not for content changes. Accomplishing this required a simple revamp of the GitHub Actions I had created.

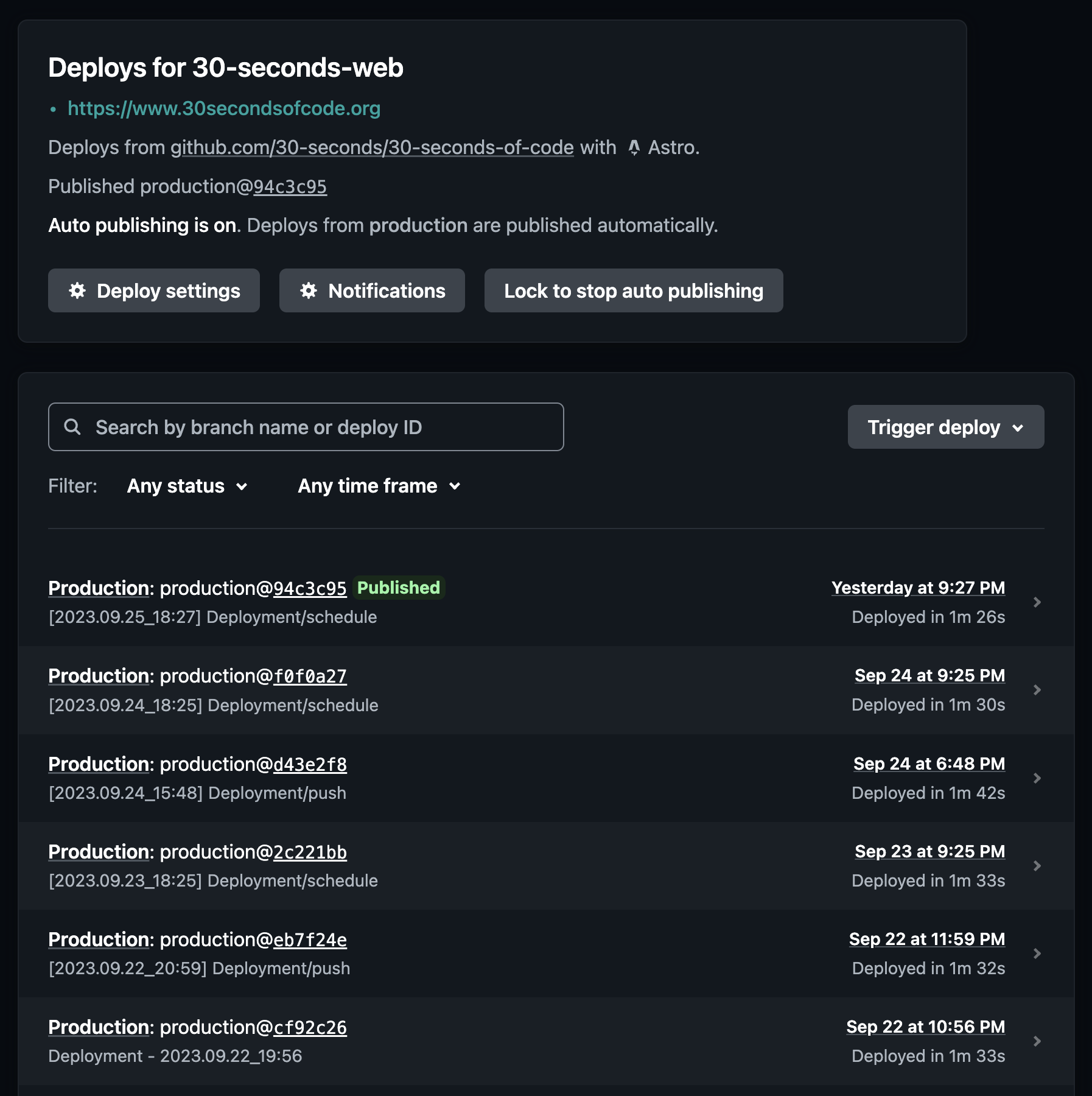

The scheduled and manual deploy workflows were merged into one. This workflow triggers as needed via cron or manual action and will always trigger a deployment to Netlify via a commit in the production branch. The push-based workflow, however makes use of the Paths Changes Filter, along with some rules to only trigger deployments if any of the website-related files have changed. This prevents minor changes in content files triggering a deployment. Finally, both workflows now output the triggering event as part of the commit message, so that it's easier to track what caused a deployment.

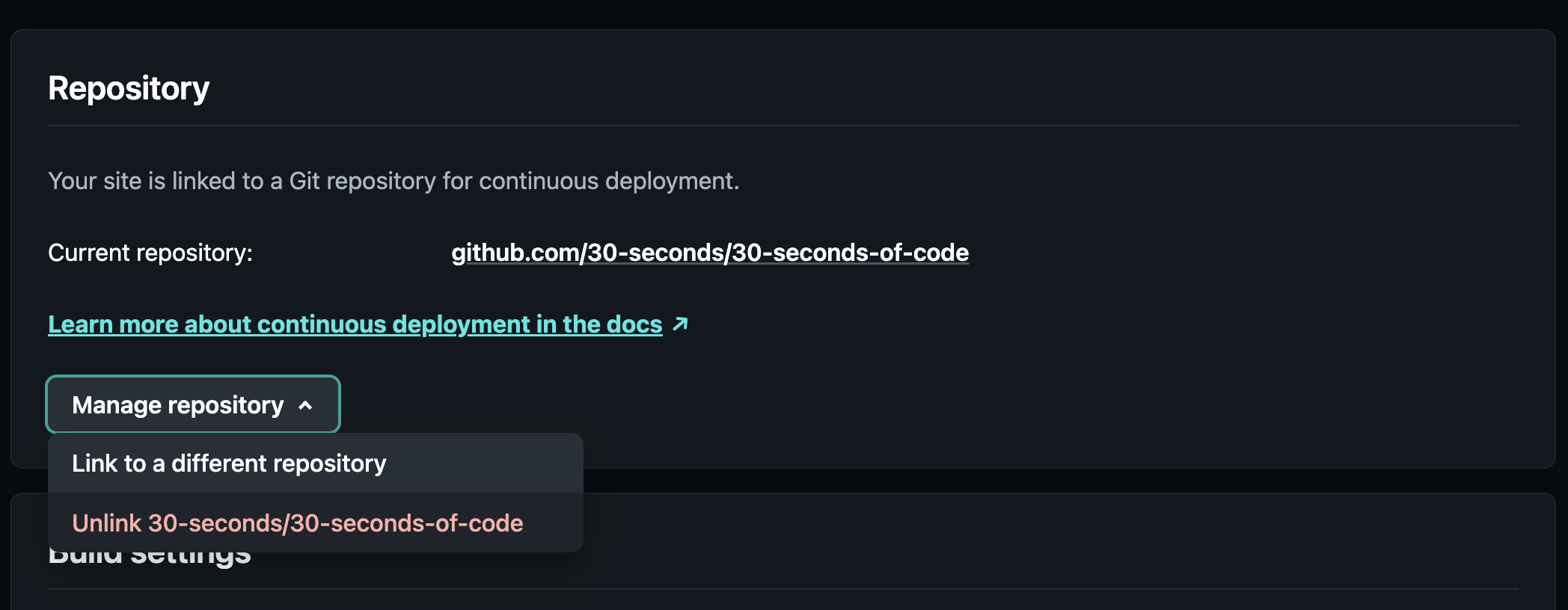

Another point of interest is the changes that I had to make to the Netlify configuration. I was very skeptical if this would require a lot of manual work, but luckily I could change the repository I deploy from via the platform's UI. This only took a couple of minutes, caused no downtime for the website and needed no DNS changes, as everything was already configured.

Trivia

I was at the time working on some new GitHub Actions that would allow for pull request QA checking, making content curation much simpler. These would be canned later, as community contributions were put on the back burner.

Towards the end of this period, I transferred the 30-seconds-of-code repository back to my personal account. Links to the previous URL will link to the new one, as long as the organization still exists on GitHub, which is the reason why I'm not deleting it.

Quality of life improvements Late 2023

Tools: Astro, jsiqle, Netlify, GitHub Actions · Commit reference

During the last few months of 2023, a lot of quality of life changes were made to the website, affecting end users (UI changes), authors (content creation tooling), infrastructure (content parsing and building) and development (hot reloading and content queries).

Some changes that were made include, but are not limited to, an updated MarkDown parser, the addition of automated CodePen embeds, GitHub-style admonitions, watch mode for content hot reloading, and prepared queries for the console.

Additionally, the codebase was migrated to ESM, while a rewrite and restructure was done to ensure everything worked as intended. Finally, some unnecessary integrations (Google Ads, Google Analytics) and infrastructure parts (icon font, second content font, multiple format images, executable snippet code) were removed from the codebase altogether.

Trivia

Some of the remark plugins were (and still are) written in a very trial-and-error sort of way, where I try to figure out what nodes are produced by the parser and what I can do to transform them. I often resort to adding raw HTML into the output, which is not ideal and could definitely be improved.

CodePen embeds needed some styling, as to not clash with the website color palette. The documentation for embedding and using them is scattered around, outdated and often incorrect. I had to delve into code and tinker a bit with them to get it right.

Watch mode was implemented in an arbitrary fashion, making it slow and a little fiddly. However, it provided enough utility to keep around until later iterations, where I could make it more elegant and practical for my needs.

Rewrite in Ruby on Rails Mid 2024

Tools: Astro, Ruby on Rails, SQLite, Netlify, GitHub Actions · Commit reference

After about 6 months of working on cleaning up and consolidating content, I decided to try an infrastructure change, namely rewriting all of the backend code in Ruby on Rails. The idea was to create a JS - Ruby on Rails - JS (Astro) sandwich.

The first JS part would be responsible for parsing MarkDown and highlighting content, much like before, so I wouldn't have to replace this part of the infrastructure, which worked well. The output of this step would be a JSON file, same as before. Some optimizations were made to parallelize code execution and separate this logic into what was essentially a standalone module that could run, process input, finish and exit.

Ruby on Rails would then replace the jsiqle part, using its ActiveRecord and SQLite to load the JSON data into a persistent storage. The SQLite storage would be treated as a throwaway layer, meaning it would be regenerated on application restart. This allowed the code to interface nicely with the latest data and easily use ActiveRecord helpers.

Finally, rake tasks and serializers were used to output JSON data in the same structure as before to then feed into Astro.

Trivia

While this approach made it a lot easier to query data and optimize structures, it was relatively slow, mainly due to the I/O overhead needed for the additional SQLite step.

Build times with Ruby on Rails were about 3x slower than JS prior to them and about 4x slower than the optimized JS code that shipped after the next refactor.

Migrating from JS to Ruby on Rails provided a great opportunity to separate concerns and build steps into the initial parsing (JS), data processing for serialization (Ruby on Rails) and Static Site Generation (Astro). This allowed for further refactors, where these three steps are separate.

Due to the way the refactored codebase was set up, I never managed to crack the code of how to add a watch mode. This, however, wasn't a problem, as this setup was really short-lived.

Rewrite back in plain JS Late 2024

Tools: Astro, Netlify, GitHub Actions · Commit reference

Seeing that Ruby on Rails was slow for my use case, I started migrating the Ruby code back to JS. The Ruby on Rails directory structure provided a great way of organizing files, logic and figuring out what goes where, so I kept most of the conventions and structures intact.

Porting from Ruby back to JS took about a week, right before the summer break, and it was not particularly hard, as I was relatively fluent in both languages. The performance improved quite a bit, even compared to the setup I had prior to the Ruby on Rails rewrite.

A notable update at this time is the custom model system I developed, inspired by the previous ActiveRecord implementation, which is thoroughly documented in the Modeling complex JavaScript objects series of articles, written in late 2024. This system essentially replaced jsiqle, which was far too slow due to the usage of Proxy and being agnostic, while a custom-tailored built-in solution was way faster. The performance increase was only compounded by the use of new JS features (e.g. static initialization blocks) that made the code more robust, less verbose and significantly more customizable.

I kept working on small changes, while revising content, for a few months, most notably adding a better watch mode. The new watch mode watches all files under the content directory for changes. When a change is detected, the JSON data needed for Astro is recalculated on the fly, by rerunning the entire processing pipeline, skipping assets and other things that aren't important to improve response times.

Trivia

Notifying Astro about changes in content was tricky. To circumvent the issue, I devised a trick where a timestamp.js file is generated at the end of each content rebuild. This is then imported into Astro, so that it notices a dependency change and it will reload the page.

The new watch mode delivered a near-instant editing experience, where switching from VS Code to Chrome (literally under a second) would be enough to rebuild the content and trigger an Astro page refresh, on a MacBook Air M1.

During this time, the Update Logs functionality and announcement on the home page was introduced, allowing for a more personal touch.

While the 2-step content preparation (MarkDown parsing, serialization from models) was still made up of distinct, decoupled steps, the watch mode didn't make use of this separation. To this day, the separation of the layers is intact, yet only needed as a means to debug parts of the pipeline more easily during development of new features.

In late December, I redesigned my personal portfolio website to match the style and color palette of 30 seconds of code, as part of the greater strategic shift in the brand narrative (30 seconds of code now being a personal blog and all that) to feel more concise and like part of the website itself. Fun fact: My personal portfolio website also doubles as a printable CV, with custom print styles to be easily exported to PDF.

Functionality extensions Early 2025

Tools: Web Components, Astro, Cloudflare, GitHub Actions · Commit reference

In the months that followed, I focused more on content rather than infrastructure. However, as I focused on larger projects, I also liked tackling more challenging tasks, which also lead to some infrastructure projects that really upgraded the website.

One such project was the complete search overhaul, as the previous search system dated back to early 2020 and was severely underpowered for the now long-form content and the the sheer amount of articles it had to serve. I developed a new Natural Language Processing (NLP) solution with TF-IDF for this purpose, building a document index, inspired by ElasticSearch, which was later enhanced with partial matching via n-grams. The new search journey is documented in this series of articles, written at around the same time as the implementation.

Another major overhaul was the removal of PrismJS in favor of Shiki for code highlights. This provided better grammars and syntax highlighting, allowing for more accurate, VS Code-like highlights. It also unlocked many new features, such as bracket pair colorization, line highlights, collapsible code blocks etc.

Moreover, another addition was support for Web Components to enhance the content on various pages. These include, but are not limited to, the table of contents scroll spy, code tabs, dynamic LaTex support, Baseline support and step visualization. All components are loaded dynamically, as needed, alongside their CSS via ECMAScript Modules (ESM), while having accessible fallbacks, in case anything goes wrong. Apart from these, I also developed a way to link to different articles and collections via custom MarkDown syntax, allowing for more interesting links between articles.

Finally, I moved the website to Cloudflare Pages for hosting, as it provided a better experience and more features than Netlify (namely integrated Web Analytics and AI Bot protection). The website is now served from Cloudflare's edge network, which provides faster load times and better performance. Their bandwidth and usage limits are pretty generous, so I don't expect to run into any issues with the current traffic any time soon. The whole migration process took just one evening, with most of the issues I faced being related to DNS setup that I'm not particularly good at.

Trivia

I plan to enhance the NLP setup to later introduce topic modeling, embeddings and dynamic personalized recommendations, based on the current user session.

The search system still runs on the client, using a serialized JSON. I kept the original setup mostly intact, however I had to find a good balance between quickly setting it up on the client and minimum network load. I settled a frequency mapping system that makes it easier to reconstruct the document index on the client, without having to serialize huge loads of data for it (e.g. i:2 know:2 that nothing).

Shiki's codebase is a little tricky to browse and the documentation wasn't very accessible for my needs. I ended up reading most of the codebase to make sense of it. I also didn't like how some official transformer plugins were implemented, so I rolled up my own whenever possible (example).

I wanted code tabs to work in the most frictionless way possible. This meant that I had to use a details element to wrap them, which made me resort to some pretty clever and complicated hacks to make them work. A simplified implementation is documented here.

LaTex libraries are extremely heavy, so build times, especially in watch mode are terrible. It's not optimal to load the library on the client side, but it only happens in the few (~10) articles that need it and is also cached by the browser.

Remember how I removed PrismJS? Well, I lied... a little! Watch mode still uses it in the form of a Web Component for faster edit time page refreshes. There is now a watch mode and an observe mode, using PrismJS and Shiki respectively.

I updated Sass to the latest version at this time and I gotta say their automatic migration tools and migration guidelines are a breeze to follow.

A lot of these later updates are documented in the website's Update Logs.

Phew! That was a ton of information, especially considering it's almost 8 years worth of work, mistakes, learnings and experiments. I hope you found this article interesting and that you'll take away some useful insights that you can apply to your own projects. See you in the next one! 👋